Some Recent Syllabuses

Contemporaneities

Goldsmiths 2020–21

The events of May 1968 in Paris, across Europe and beyond are regarded as pivotal in the development of how we understand resistance, power and subjectification after Enlightenment humanism and modern structuralism. This week we will look at this foundational moment for European thought and grass-roots politics. We will consider the events themselves, with particular reference to the legacy of Situationism and the posters from the ‘Atelier Populaire’ (the occupied printroom of L’École des Beaux-Arts). But we will also attend to what preceded and followed the short-lived events, in particular the Algerian war of decolonisation (1954–62), and the establishing of the University Paris VIII under the directorship of Michel Foucault (in 1969). As such, we will consider the theoretical and historical critiques of power that emerged in these years, the ways in which guerilla warfare and street protest construct urban space against early-modern architecture and town planning, and the role of educational institutions, students, immigrants and workers in effecting social and institutional change through direct action.

Required Reading

Wahl, Jean. “Introduction”, The Philosopher’s Way (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1948), xi–xiv.

Laâbi, Abdellatif. “Realities and Dilemmas of National Culture I & II” [1966; 1967], Souffles-Anfas: A Critical Anthology from the Moroccan Journal of Culture and Politics, edited by Olivia C. Harrison and Teresa Villa-Ignacio (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016), 61–73; 95–103.

Foucault, Michel, “Politics and Ethics: An Interview” [1983], The Foucault Reader, edited by Paul Rabinow (London: Penguin, 1991), 373–380.

Into the 1970s a question first broached by the Surrealists resurfaced concerning how to think with the works of both Freud and Marx about the constitution of subjectivity – that is, to ask how we might understand that the “individual” is made up by material, social relations as well as by the workings of the unconscious. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari combined their knowledge of poststructuralist philosophy, transcendental empiricism and (anti)psychiatric practice to propose a model of the unconscious as “machinic”. This week we will examine their idea that desire is produced, rather than “played out”, in the subject, and briefly consider the influence of some key figures in Guattari’s thought: his one-time mentor, Jacques Lacan; Frantz Fanon (who trained alongside Lacan); and Jean Oury. We will also look at the March 1972 issue of the journal Recherches, entitled “Three Billion Perverts: An Encyclopaedia of Homo-Sexualities”. As editor of the issue, Guattari faced prosecution, and all copies were ordered to be destroyed as obscene and “sexually deviant”. We will consider how the texts in that publication have been taken up in some queer theory, as well as how Deleuze and Guattari’s work influenced the radical reorganisation of a number of psychiatric institutions in the 1970s and beyond – paying particular attention to the role of art in those projects. Finally, we will consider how Deleuzo-Guattarian “schizoanalysis” has been mobilised as a mode of art criticism concerned with the “asignifying” and “affective”.

Required Reading

Foucault, Michel. “Preface”; Seem, Mark. “Introduction: The Anti-Ego”; and Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari “The Desiring Machines: 5 The Machines”, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Helen R. Lane, Robert Hurley and Mark Seem (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 1983), xi–xiv; xv–xvii; 36–41.

Guattari, Félix. “Psychoanalysis and Polyvocality”, The Anti-Oedipus Papers, edited by Stéphane Nadaud, trans. Kélina Gotman (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2006), 101–2.

Lacan, Jacques, “Seminar on ‘The Purloined Letter’” [1955–57], Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English, edited and translated by Bruce Fink, Héloïse Fink and Russell Grigg (London: W. W. Norton and Company, 2006), 33–35.

The 1970s and 1980s in Britain and further afield saw a stark rise in two apparently different forms of fluidity. On the one hand a reinvention of bodies in terms of their posthuman, cyborgian and non-binary potential was occurring in film and on dance music scenes; and on the other hand, there was widespread deregulation of markets (Thatcher-Reagan) and the rise of complex, computationally assisted financial products (Black-Scholes formula). This cyber-positivism and emergent neoliberalism happened against a backdrop of deindustrialisation and unemployment, with varying cultural-political responses, both dissenting and mythopoeitic – from the miners strikes to Detroit techno. As such, these decades established our current imperatives of speed and the dematerialisation of bodies.

This week, we will examine terms like “neo-liberalism” and its relationship to more recent ideas of acceleration/prometheanism and Alt-right/Art-right; and we will look at representations of the 70s/80s in the media and the arts – from the BBC misrepresentation of the Battle of Orgreave to Jeremy Deller’s 2001 re-enactment of it, as well as his Acid Brass project.

Required Reading

Noys, Benjamin, “Cyberpunk Phuturism”, Malign Velocities: Accelerationism and Capitalism (Ropley: Zero Books, 2014), 49-62.

Virilio, Paul, “The Dromosphere”, The Original Accident (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007), 83-101.

The 1990s and the rise of New Labour saw the consolidation of the neoliberal ideology in British politics and the mainstreaming of much alternative culture – this latter often based on nostalgia and retromania. This week we will discuss the emergence of the Young British Artists through the Freeze show (1988) and their patronage by advertising mogul Charles Saatchi (who saw Thatcher to victory in 1979 with the slogan “Labour isn’t Working”). We will consider how the height of the establishment’s courting of the YBAs and the mainstreaming of alternative culture happened alongside the dissolution of the contract between working-class youth and intellectualism which the art schools of the 1970s and 80s had represented. We will also look at how the notion of “Brit” which crystallised in these years was exploited in the Brexit referendum.

Required Reading

Hatherley, Owen, “Introduction”, Uncommon (London: Zero Books, 2011), 1-22.

Youtube playlist: "From Three Lions to Vindaloo".

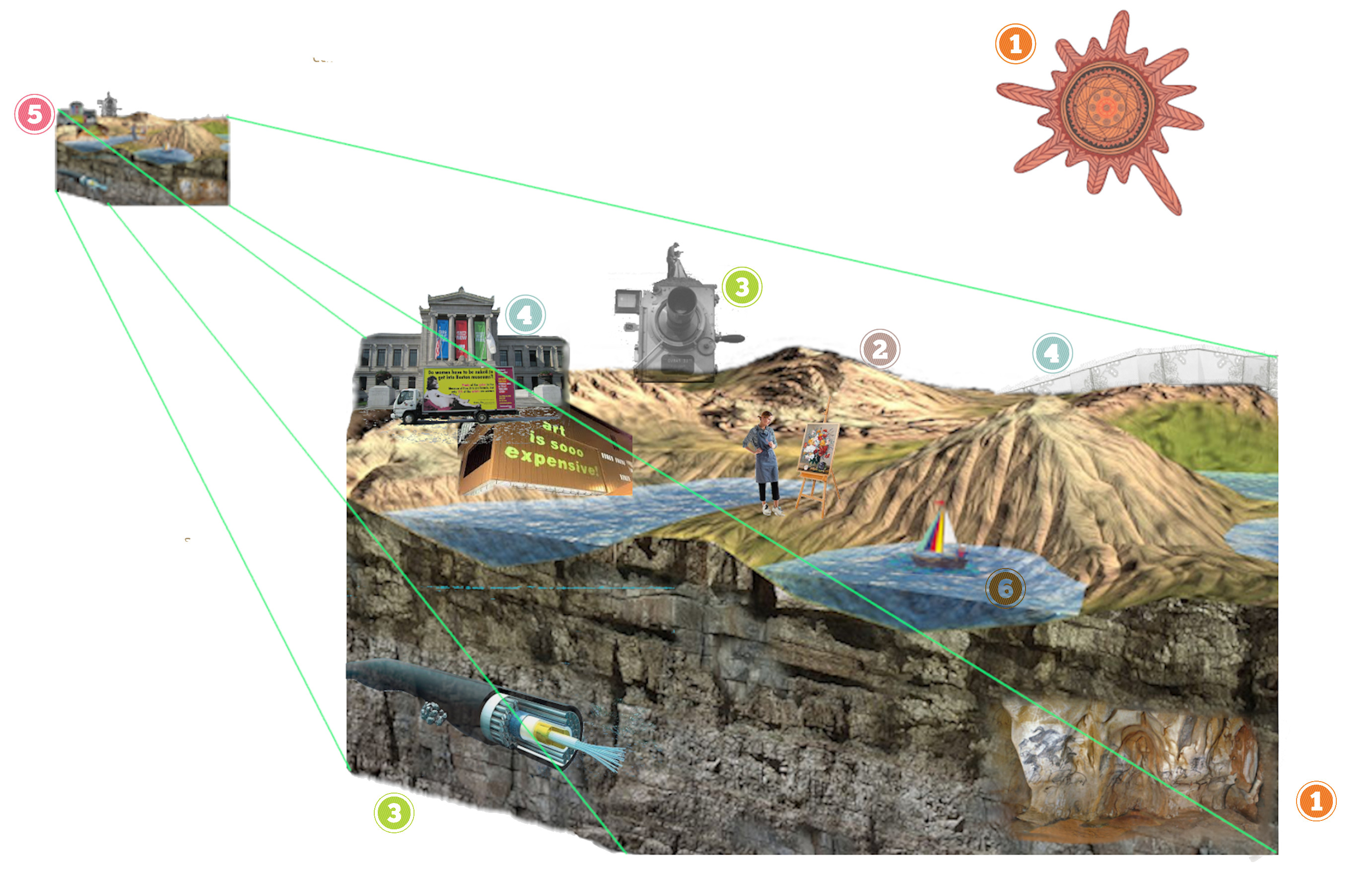

Our planet itself is already the mega-structural totality in which the program of total design might work. The real design problem then is not foremost the authorship of a new envelope visible from space, but the redesign of the program that reorganizes the total apparatus of the built interior into which we are already thrown together.

Benjamin Bratton, The Stack

This week we will consider the material impact of humans, capitalism and information technologies on the Earth and consider how other abstract and real totalities such as the Globe, the World and the Planet have been reformulated through these emergent notions of movement, un/regrounding, porosity and flow. We will be asking how some of ideas and practices we have looked at in previous weeks are being expanded through consideration of nonhuman and nonvital agents.

Required Reading

Wark, Mackenzie. “The Stack to Come.” Public Seminar (December 2016)

Parikka, Jussi, “2. An Alternative Deep Time of the Media”, Geology of Media (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 29–58.

Perma | Culture

West Dean MFA Year 1

Spring 2020

We will begin this block of lecture-seminars by considering two historical turns in human relations to the land, both of which highlight ways in which culture not only reflects but shapes – and even exploits – nature. On the one hand, we will look at the ways in which land was entered into political economy (with particular attention to Marx’s notion of “primitive accumulation” and Karl Polanyi’s notion of “fictional commodities”). And, on the other hand, we will dissect the ways in which representing landscapes has, in turn, shaped the land: how did Land become property and picture; how are these two related; and how can we observe them being illustrated and leveraged in visual culture? With Silvia Federici we will ask how women in particular have historically been affected by these changes, and how stereotypes about feminine characteristics and labour-value have been produced and challenged in relation to the land.

Required Reading

Silvia Federici, “Preface” to Caliban and the Witch (Brooklyn, ny: Autonomedia, 2004), 7–10.

W J T Mitchell, “Introduction” and extract from “Imperial Landscape” in Landscape and Power (Chicago, il: Chicago University Press, 2002), 1–10.

Screening

Winstanley (1975), dir. Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo (92mins) + Making of Documentary (13mins)

This week we will consider the problems of thinking about the scale and immanence of climate catastrophe; the ways in which artists have represented, communicated and made tangible the enormity of climate change; and how this has engaged with earlier notions of the sublime. We will also consider the continuities and differences between the rhetoric and fear around climate change and other apocalyptic pronouncements – such as Millenarianism, Seventh Day Adventism and the Branch Davidian cult, and the Y2K Bug – to consider how artists construct their notions of apocalypse.

Required Reading

Amitav Ghosh “Part I: 1–4”, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable (Chicago, il: Chicago University Press, 2016), 3–11.

Hans Magnus Enzensberger “Two Notes on the End of the World” [1978] trans. David Fernbach in Critical Essays eds. Reinhold Grimm and Bruce Armstrong (New York, ny: Continuum, 1982), 233–241.

We will consider the ways which nature has been engaged with in Japanese art, from the poetry, painting and photography of the Edo (1603–1868) and Meiji (1868–1947) periods to post-WW2 experimental and performance art practices. In particular, we will ask if there is a model in these various practices, for being simultaneously of nature and distanced from it (ie, by our gaze or by a reliance on technology). We will position this attitude in relation to the twentieth-century Kyoto school philosophers and their combining of Western and Eastern philosophical traditions.

Required Reading

Reiko Tomi “Prologue” in Radicalism in the Wilderness: International Contemporaneity and 1960s Art in Japan (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016), 1–10.

Yuriko Saito “The Japanese Appreciation of Nature”, British Journal of Aesthetics Vol. xxv, No.3 (Summer 1985): 239–251.

Workshop: Collective Listening

We will reconvene after lunch to listen to and discuss a variety of music that engages with land and place. We will consider and discuss diverse artists and modes, from the folk music of Sussex to Afrofuturism, and from pastoral symphonies to contemporary ambient. Artists will include Shirley Collins, Catrin Finch and Seckou Keita, Sibelius, Laura Cannell, Miles Davis, Freddie Hubbard, Jana Winderen, Ande Somby, Brian Eno and Richard Skelton.

This week we will consider the ways in which experimental and low-impact farming and ruralism have drawn on and been presented as art practices. We will look at the origins of contemporary permaculture and at the ways in which cultivation and creation are thought about by artist Gianfranco Baruchello and Pierre Creton. We will also consider more urban critical and activist projects such as those of Critical Arts Ensemble and guerilla gardeners.

Required Reading

Wendell Berry “Preface” and Mansanobu Fukuoka “Chapters 1–4” in Mansanobu Fukuoka The One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural Farming [1978] trans. Larry Korn (New York, NY: New York Review of Books, 2009), xi–xv, 1–18.

Gianfranco Baruchello and Henry Martin, How To Imagine: A Narrative on Art, Agriculture and Creativity (New York, NY: McPherson, 1984), vii–ix, 1–13, 53–68.

Screening

Va Toto! (2016) dir. Pierre Creton (96 mins)

This week we will ask how ecological ideas of “rewilding” can be embraced in art – not necessarily as its subject, but integrated into our ways of making and modes of being. We will consider the meaning of and connections between rewilding our making practices and rewilding our ways of thinking. How can we think in ways that are coherent but not bound by rationalisation and machinic logic? How might we approach our materials as if they were something other than inert “stuff” available to us to do with as we wish? Ultimately, in what ways do our practices not only rely on the Planet, but return something to it? How can art be thought and practised as a looping back in, as the immanence of nature and culture?

Required Reading

Isabelle Stengers “Reclaiming Animism”, e-flux journal #36 (July 2012)

Peter Gray “Rewilding Witchcraft” [2014] in The Brazen Vessel (Scarlet Imprint, 2019)

Plant collection, classification and cultivation has, historically, often been tied up with privileged colonial exploration and structures of scientific knowledge which seek to rule on what is natural and belongs and what is monstrous and out of place – for example with non-profitable mutations and undesirable “weeds”. Simultaneously, the vocabulary of plants has often been used pejoratively against queer subjects. Various gardeners, artists and theorists have used these connections to explore their own queerness and to reconsider the binary relationship between “us” humans and “them” plants.

Required Reading

Gay Plants ’zine

Verena Andermatt Conley, “Hélène Cixous: The Language of Flowers” in ed. Laurence Coupe The Green Studies Reader (London: Routledge, 2000), 148–153.

Workshop

Raspberry Pi: Entry-level Micro-computing for Artists

In this final week we will consider the ways in which time, memory and imagination are tied to place, and how temporality and spatiality intersect and produce each other. In particular, we will consider art works and ideas concerning how – through habitation, staging and exploration of place – the future and the past can be put into contact with each other, by-passing the terminal constraints of the present.

Required Reading

Simon O’Sullivan “Myth-Science as Residual Culture and Magical Thinking” in Postmedieval: A Journal of Medieval Cultural Studies, Vol. ix, No. 4 (2018).

Optional Reading relevant to both morning and afternoon sessions:

Russell Hoban Riddley Walker [1980] (London: Bloomsbury, 2012).

Workshop

Experimental Encounters – In Search of the Hart of the Wood

We will head into the arboretum and grounds of West Dean to discuss and explore the fourfold which Russell Hoban offers in Riddley Walker: the heart/hart of the wood/would, that is the coming together of the fleeting and actual, the planet and human desire or project.

Care: From Labour to Ecology

West Dean MFA

Spring 2022

In his most recent book, Boris Groys argues that the predominant ways of thinking about the art of modernity – as avant-garde, rule-breaking and heroic – are either antagonistic or indifferent to the preserving impulses of care. In setting art apart from the social in this way – as rebellious or vanguard – artists are cast as a different class of person: a class liberated from the duty of maintaining the present, and a class liberated or otherwise dis-invested from the values of the present. This view of art, once the basis of its reputation for progressivism and radicalism, risks becoming evidence of its complicity in the worst ravages of neoliberal inequality and indifference.

At the same time, it indicates not only our difficulty in thinking about the radicality of care – an increasingly important task – but also indicates the ways in which art is available for the laundering of reputations and the forging of alibis.

Art is increasingly found in situations of care. Yet so often it appears as a cheerful activity or as decorative objects to set the tone of institutional spaces – a promise that these institutions are not constrictive, wasting and even cruel, but are creative, nurturing and liberating. Yet, here, art and art practice are often afforded only a utilitarian role: art is decorative to the point of being anodyne, or it is timetabled as entertainment, recreation or, especially with children and non-speaking people, at best a diagnostic tool. Whilst we should not hurry to disparage these purposeful uses, it also behoves us to remain alert to the wider possibilities of art – in the context of care and beyond.

We might ask, for example, if there are ways in which art and care are more fundamentally bound together as ways of being in the world? Do they have analogous functions in society? Might we think of art as, in itself, a mode of care and interdependence? Might art offer us ways of critiquing and modifying contemporary injunctions to practice "self care"? Do questions of how, for whom and why resonate between care and art in notable ways?

By thinking critically about care and about art simultaneously, we will reconsider questions pertaining to the utility of art, the place of the artist in society, our relation to ourselves and others, and the rights of nonhuman persons.

Required Reading

John Merrick “Care Work, Crewe and the Deindustrialised Economy“ https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/5100-care-work-crewe-and-the-deindustrialised-economy

We will use this initial session for two purposes:

Firstly, we shall collectively decide on the parameters and expectations of the sessions. What will help us to ensure that seminars are experienced as safe and caring spaces? How do we ensure that voices are welcomed and heard? What expectations do we have of ourselves and others? How do we discuss subjects that touch on deep-held beliefs and potentially complex and upsetting emotional territory? Does ‘ally’ belong as part of the model of ‘student’?

Secondly, we will begin to discuss what we mean by care, how definitions of care determine or ‘frame’ the recipient of care, the ways in which care might be thought beyond an active—passive binary, how care has become a transactional relationship (especially through the contemporary service economy), and how in thinking through these questions, we might think more deeply about the relation between care and art.

Required Reading

Maggie Nelson [frontispiece poem by George Oppen] + “Art Song” in On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint (London: Jonathan Cape, 2021), frontis, 19–29.

Tom Shakespeare “The Social Model of Disability”, Disability Studies Reader, ed. Lennard J. Davis (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017), 214–221.

Boris Groys “Revolutionary Care” in Philosophy of Care (London: Verso, 2022), 93–100.

There has been a historic assumption that care be done for free, and that this care be undertaken by women and within the family. Extending the tradition begun by Silvia Federici et al in their Wages for Housework manifesto, Harry Josephine Giles offers a critique of the intersections of capitalism and gender transitioning. We will consider this diagram of care-as-resistance alongside an earlier example of ‘queering’ care, namely the ‘elective families’ of New York’s Ballroom scene as depicted in the film Paris is Burning.

With this latter document, especially, we will consider the importance of joy as a caring and resistant mode of togetherness; though we will also acknowledge the concerns raised by bell hooks about the film and the ‘white gaze’.

Required Reading

Harry Josephine Giles “Wages for Transition“: https://harrygiles.files.wordpress.com/2019/12/wages-for-transiton-download.pdf(please note that HJG donated over 40% of their commission for this text to Action for Trans Health. You can read more and donate to the cause’s Solidarity Fund, here: https://actionfortranshealth.org.uk/fund/)

bell hooks “Is Paris Burning” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston, MA: South End Press, 1992), 145–156.

Screening

PARIS IS BURNING, dir. Jennie Livingston, 1990

If the ‘elective families’ of 1980s New York were a means of overcoming the reactive expulsion of the queer individual from the ‘family’ and forging an affirmative, collective subjectivity (the House), in the decades since, we have seen a much more widespread outsourcing of care, as the normative family unit ceases to be able or inclined to service itself, amidst myriad demands on time and emotional investment.

As in many service sectors, this skilled, physically demanding yet poorly-paid labour is taken on by women from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, and especially those from Eastern Europe, Africa and South-East Asia. As a result, this globalisation of labour makes visible an acute contrast in family values: the migrant labourer cares for somebody else’s elders or children in order to support her own.

This week we will consider migrancy, globalisation and family, and ask how different models of care and reproductive labour mingle and co-exist. Again, the same questions will be asked of the globalised art world.

Required Reading

Rhacel Salazar Parreñas “The Care Crisis in the Philippines: Children and Transnational Families in the New Global Economy“, Global Woman: Nannies, Maids and Sex Workers in the New Economy, eds Arlie Russell Hochschild and Barbara Ehrenreich (London: Granta, 2003), 39–54.

Eileen Boris extracts from “6. Home” + “7. Women’s Place (in the Future of Work)” in Making the Woman Worker: Precarious Labor and the Fight for Global Standards, 1919–2019 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 193–197 + 229–233.

Svetlana Pimkina and Luciana de la Flor “Executive Summary” + “Carework”, Promoting Female Labor Force Participation (Washington, DC: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank, 2020), 5–6, 14–17.

Building on the activism and solidarity seen in the ILO, this week we will consider the mutual aid movement and the boots-on-the-ground work done throughout the first years of the covid-19 pandemic. In particular, we will be concerned with how community and creativity have characterised these groups, and within communities who do not identify as ‘mutual aid’. We will engage in the debates which contrast charity and mutual aid, and play with the idea of ‘ethico-aesthetics’ in order to think about how social relations and the arts are mutually constitutive of a wider territory.

Required Reading

Dean Spade ‘Introduction’ + ‘Solidarity not Charity’ in Building Solidarity During This Crisis (and the Next) (London: Verso, 2020), 1–5; 21–29.

(With Radical in Progress, Spade has prepared a set of questions and exercises aimed at prison reading groups. We will spend some time in the seminar looking at the Group Exercises section at the end of this study guide: http://v.versobooks.com/Mutual_Aid_Prison_Guide.pdf)

I would also strongly recommend the (dubiously titled) ‘mad map’ section of the book, which has excellent advice for reflecting on your attitudes to work, creativity and self-worth: pp127–141.

Vanessa Zettler ‘On Grassroots Organizing: Excerpts from Brazil’ in Pandemic Solidarity: Mutual Aid during the Covid-19 Crisis eds Marina Sitrin and Colectiva Sembrar (London: Pluto, 2020), 249–264.

Screening

NIGHTCLEANERS, dir. Berwick Street Collective, 1972–75.

As Michel Foucault so perspicaciously observed in 1978, neoliberalism is characterised by the injunction to become ‘entrepreneurs of ourselves’. Certainly, Foucault overstates the extent to which this is the sole characteristic we should concern ourselves with; but stressing it allows him to place the phenomenon in a longer tradition of the particular ethics of freedom that he calls ‘the care of the self’ – that is, the practices and rituals through which we construct ourselves, and into which the state and capital have increasingly interpellated themselves. He begins this history by talking of epistolary self-writing traditions in Ancient Rome, and brings it to the present of ‘homo ɶconomicus’ for whom, he argues, power has penetrated every corner of life, down to our sense of self and the engineering of our desires – a theme he calls ‘biopolitics’.

To grasp this long view, we shall look at a conversation with Foucault in which some of his ideas on self, ethics and aesthetics are articulated; and to introduce the pressures on the self as they appear in contemporary life, we will look at a polemical yet conflicted theory-memoir in which the author contemplates his engagement with ‘mindfulness’ as a practice and an industry.

Alongside these conceptual and political approaches, we will look at a number of contemporary artworks that consider the performance of self-care. As such, we will also have cause to return to the work of Maggie Nelson, as discussed in our first session of this semester.

Required Reading

Michel Foucault “On The Genealogy of Ethics: An Overview of Work in Progress” [1983] in The Foucault Reader ed. Paul Rabinow (New York, NY: Pantheon, 1984), 340–351.

Ronald E. Purser “Mindfulness as Social Amnesia” in McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality (London: Repeater, 2019), 103–114.

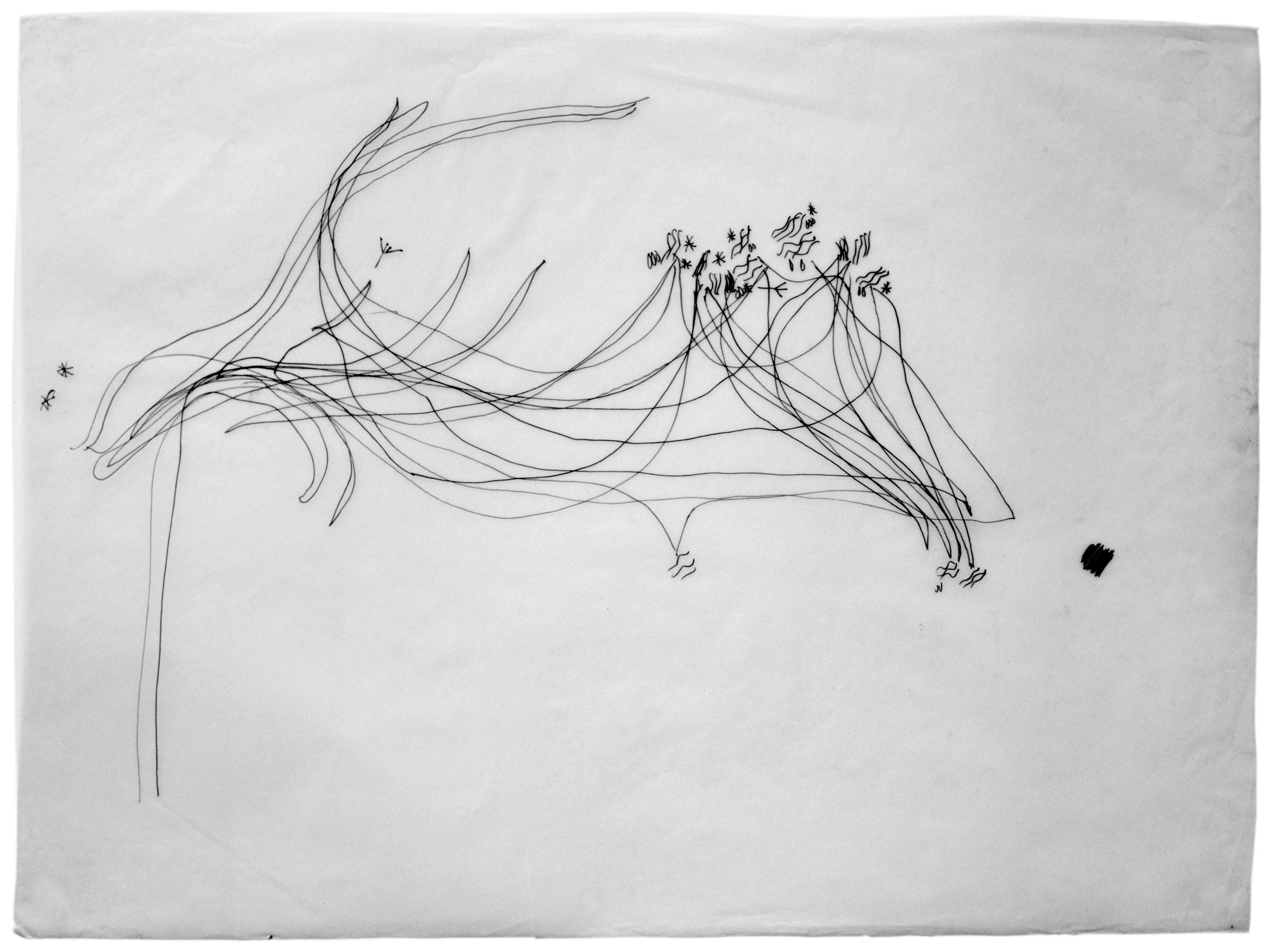

Working adjacent to the (anti)psychiatry movements of the 1960s and ’70s, Fernand Deligny was committed to developing innovative and ethical ways of working with autistic children. Like Jean Ury and Felix Guattari at the La Borde clinic and Franco Basaglia at Gorizia, Deligny pursued a ‘flat’ model of organisation without doctor\patient hierarchies, and foreshadowed more recent user-led, self-advocacy movements like Mad Pride and ASAN.

We will concentrate on Deligny in particular because his writings have only recently become widely available in English translation; and because the way in which he understood the autistic child’s sense of self, and developed inclusive notions of difference, drew on his acute interest in the actuality of drawing as a mode of expression and world-making. Here, art is the basis of care, and drives the elaboration of ways of being-together in which normative notions of self and other – and the power differentials they enact ’ come under scrutiny.

Required Reading

Fernand Deligny “Art, Borders ... and the Outside” + “Card Taken and Map Traced” in The Arachnean and Other Texts trans. Drew S Burk and Catherine Porter (Minneapolis, MN: Univocal, 2015), 145–154.

Leon Hilton “Mapping the Wander Lines: The Quiet Revelations of Fernand Deligny”, LA Review of Books (2 July 2015): https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/mapping-the-wander-lines-the-quiet-revelations-of-fernand-deligny

Fèlix Guattari “La Borde: A Clinic Unlike Any Other” [1977] in Chaosophy: Texts and Interviews 1972–1977 trans. David L. Sweet (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2009), 176–181 + 191–194.

In this session we will ask a variety of questions about the classifications, protections and relationships we have with animal others, and the myriad ways in which ‘care‘ underlies, shapes and is defined by these relationships. We will look at the work of Donna Haraway, in particular her interest in technology and institutional power; and at the remarkable work of Temple Grandin, especially that concerning farm animals, human autism and the visual.

Required Reading

Donna Haraway “11. Becoming Companion Species in Technoculture” in When Species Meet (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 275–284.

Temple Grandin “Thinking in Pictures: Autism and Visual Thought” + “Foreword” by Oliver Sacks in Thinking in Pictures: And Other Reports from My Life with Autism (Expanded Edition) (New York, NY: Vintage, 2006), 3–32 + xiii–xviii.

We have spent much time trying to look beyond active/passive binaries of care, and to think about ungrounded or decentred networks of ethical relations. In this final session, we will also attempt to think outside of the timescale of individual lifetimes. We will discuss the ‘seven generations’ clause of the Iroquois Constitution, popularised most widely by Robin Wall-Kimmerer through her explications of the ‘Honorable Harvest’. Given that one might conceivably have lived relationships with one’s great-grandparents and great-grandchildren (hence seeing seven generations in one’s lifetime) we will also ask how care, ethics and aesthetics might relate us to the unrelatable – the deep pasts, deep futures and the unthinkable scales of the Planet? How might we go about developing a comportment of care that considers the radically unknowable, unthinkable, unrelatable? How, ultimately, does ‘care’ become extended to material and immaterial ‘world care’? And what might this mean in artistic and political practice?

Required Reading

Marìa Puig de la Bellacasa from “Soil Times” in Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2017), 169–177.

Rebecca Tamás “On Hospitality” and “On Greeness” in Strangers: Essays on the Human and Nonhuman (London: Makina Books, 2020), 30–38, 54–62.

Gavin Barker “A New Constitution for the UK Needs ‘Rights of Nature’ at its Heart”, openDemoncracy (28 March 2019): https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/a-new-constitution-for-the-uk-needs-rights-of-nature-at-its-heart/

A Story of (Thinking) Art, Explored as a Terrain

West Dean MFA

Autumn 2021

In this opening week, we will look at two “origins” of thinking about art: on the one hand, we will discuss the role that images and artists are afforded in the philosophy of Plato; and on the other hand, we will look at a theory of some of the earliest artworks, namely dissident Surrealist Georges Bataille’s writings on prehistoric cave paintings. Together, we will ask whether the questions of truth and magic that these two thinkers explore are, indeed, still relevant for us today in our own studio practice and the wider worlds of contemporary art.

Reading

Eyjólfur Kjaler Emilsson “Plotinus on the Arts” in ed. Thomas Kjeller Johansen Productive Knowledge in Ancient Philosophy: The Concept of Technê

(Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2021), 245–262

Insightful essay on the aesthetic theory of the greatest of neoPlatonists, with particular attention to questions of deliberation and craft.

Edith Dudley Sylla “Creation and Nature” in A S McGrade (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Philosophy

(2nd

Edition) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 171–186

A solid, readable overview of this central transitional period from Classical to Modern thought. Medieval European thought is heavily guided by commentaries on Plato et al by Arabic and Jewish scholars..

Bill Marshall (ed.) Paragraph – Special Issue: Prehistory: Art, Cultural Theory and Modernity Paragraph

Vol. 43, Issue 2 (November 2021): https://www.euppublishing.com/toc/para/44/3

Recent number of the learn

è

d journal, dedicated to the reception of prehistoric discoveries by modernist (especially surrealist) authors..

Philipp C. Grote Ice Age Art and the Bear Cult

(n.p: Ivan Morf/Self-published, 2015)

Fascinating and slightly out-there investigation of the Chauvet caves with particular reference to shamanism, the origins of “man” and the role of women in ice-age culture.

This week we will explore two moments that could be said to inaugurate the art and thought of what has been called “the long twentieth century”: namely, Paul Cezanne’s explorations of sensation and solidity, colour and form, etc.; and the propostion by Friederich Nietzsche that thought is not an archaeological search for pre-existing truths, but a productive, adventurous and expressive process of producing concepts. With this philosophical painter and this artistic philosopher in mind, we will discuss what relationship we might want our seminars and our studio practice to have.

Reading

The Letters of Paul Cézanne

(ed. Alex Danchev) (London: Taschen, 2013)

Chunky collection, well translated which shows in great detail the breadth and depth of Cézanne’s thought and his artistic endeavours..

Friedrich Nietzsche Thus Spake Zarathustra

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011)

The best English edition of the book, notable for its treatment of Zarathustra as both a rigorous philosophy and a work of poetic art.

Luce Irigaray The Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche

An immensely rich book in which intimacy replaces analysis as the primary philosophical approach to Nietzsche. Women and water alike are characterised as fluid and supple elements which conform to and exceed Nietzsche’s philosophy of creative overcoming and contact with the planet.

@the_hillwalking_hijabi

Instagram account of Zahrah Mahmood, a Glasweigan Muslim woman. Mahmood’s activities and campaigning directly challenge assumptions about the universality of access to the great outdoors in the UK. In her posts and interviews, she brings to the surface the complex entanglements of ideas on nature, nationality, belonging and green space.

This week we will consider questions concerning technology and art. We will broach questions of what has been called the “geology of media”, to think about how our materials and apparatuses position us in relation to our surroundings. Questions of materiality and framing will be relevant when thinking about our proximity to media and our bodies, and about the distance and abstractions of formal and compositional decisions.

To enagage the fully geological horizon of such questions we will ask, for example, what the difference might be between fossil fuels — the “trapped sunlight” — the “writing with light” of early photographers like Margaret Cameron, and the “envelope” of light captured by Impressionists like Manet. We will also nod to more contemporary practices which explore the intersections of material infrastructure and virtual/online life.

Reading

Susan Sontag On Photography [1978] (London: Penguin, 2019)

A highly readable collection from one of the great essayists of American critical thought; Sontag’s writing has depth and richness, but remains accessible, offering a useful “gateway” to French post-structuralist thinkers like Roland Barthes.

Kathryn Yusoff A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None

(Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2018)

A short-ish read exploring the intersections of earth sciences with feminist and critical race theories, and anticolonial history.

Vilém Flusser Towards a Philosophy of Photography

(London: Reaktion, 2000)

A reading of photography for the new millenium, considering the interaction of multiple apparatuses of image-making, reproduction and distribution, and their place in our changing culture.

Robert Mills Derek Jarman’s Medieval Modern

(Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 2018)

A provocative reading of the films, writings and art of the great Derek Jarman, with a particular accent on parallels between his queer filmmaking and his abiding interest in the cultures and privileged sites of medieval England.

We will think in particular about two kinds of border: the “soft power” borders of institutions that exclude and marginalise the bodies and artworks of certain genders, ethnicities, classes and abilities; and the “hard power” of, for example, national borders. These questions and their entanglements are deeply considered by a wide range of artists, and we will explore the ways in which such issues are explored and communicated in their work. In the context of ongoing refugee crises and renewed debates regarding “the culture wars”, we will ask how historical forms of identity politics are regarded today, what roles art may have played in previous crises, and what political and aesthetic approaches might be most effective today.

Reading

Kwame Anthony Appiah Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers

(London: Penguin, 2007)

A fast-established classic text on the question of living together, drawing on both the author’s Ghanaian heritage and the Ancient Greek philosophies of his Cambridge education.

Refugee Tales

– a series of books (ed. David Herd (Manchester: Comma Press, 2016)) emerging from the walking-and-talking events facilitated by the Gatwick Detainees Welfare Group and the indefinitely detained immigrants whom they work with: https://www.refugeetales.org/.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman The Yellow Wall-Paper (1890)

Classic “early” feminist short story, deconstructing domestic expectations from the point of view of a bed-bound woman.

Miwon Kwon One Place after Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004)

Detailed thesis on a number of art projects that critically reflect on their geographical location and the lived realities of their audiences.

Andrea Fraser “From the Critique of Institutions to An Institution of Critique” in Artforum

(September 2005): 100–106.

This week we will discuss the relationships between representations and their object, with particular reference to pop art, postmodernity, celebrity culture, big data and the post-truth political landscape. We will look at processes of simulation, real subsumption and algorithmic modelling in relation to art worlds; consider the effects these have had on culture and our sense of self; and look at artists who are actively intervening in these processes.

Reading

Hal Foster (ed.) The Anti-Aesthetic

(Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1983)

Classic collection of essays on postmodernism. At turns instructive and impenetrable. Foster’s introduction includes his famous critical distinction between postmodernism of reaction and postmodernism of resistance.

Linda Hutcheon The Politics of Postmodernism

(London: Routledge, 1989)

A well-regarded and comparatively accessible tome; particularly strong on photography, images and female desire in relation to the postmodern “end ofgrand narratives”.

Marilouise and Arthur Kroker “Way New Leftists: Interview” in Wired (Feb 1996): https://www.wired.com/1996/02/leftists/

The Canadian wife-and-husband writing unit (and founders of the seminal Ctheory.net theory website) give an interview demonstrating the delirium of contemporary culture in both the content of their arguments and the hip, neologism-heavy style of their delivery.

Edward Carey Alva and Irva: The Twins who Saved a City

(London: Picador, 2003)

A beguiling novel about twin sisters and the role played in their lives by their project to make a miniature replica of their home town. The complementary elements of adventure, craft and reclusiveness seem all the more apt today.

In the final week of this term we will consider the rise of what has been called “liquid culture”. The open water and mythic images of the sea as an under-regulated space of pirates and “monsters” have been widely adopted by advocates of “freedom” from Rousseau to Radio Caroline to the A-Vessel project; and the post-structural fluidities of gender and sexuality especially afford freedoms of self-production and intersubjective relations. It is thus both common-sensical and contradictory that liquidity and accelerated flow are also core notions in neoliberal economics, which has historically prioritised deregulation and the free movement of capital (though not, it would seem, of goods and labour). How might we navigate these myriad pictures of liquidity? How have the evolving meanings of open-ended variation and deregulation been engaged with by artists? And how might these reflections allow us to speak about freedom in relation to our art practice, artist communities, educational setting and wider lives?

Reading

Zygmunt Bauman Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty

(London: Polity, 2007)

A pithy version of the dear departed thinker’s ideas about how uncertainty rose to be the dominant social force of 21st

Century psycho-politics.

Laboria Cuboniks The Xenofeminist Manifesto

(London: Verso, 2018)

A high-octane tract which has done with biological determinism in all its forms, taking an accelerated, technology-positive attitude to the future of (post)humanity.

Rebel Roo (Nov 2016–July 2018): https://notesfrombelow.org/article/rebel-roo-bulletin

Archive of the free-sheet newspaper issued by a collective of UK Deliveroo drivers campaigning for better employment rights in the face of accelerated consumer culture and precarious working conditions.

Adom Getachew Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000)

Deep research and a bold thesis on how anticolonial struggles of the twentieth century envisaged post-nationalist approaches to world-building.

Marc Levinson The Box: How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger

(Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016)

Whopping, but surprisingly readable history of the rise of shipping containers and the re-making of the globalised world as a logistical totality.

Hands That Think, Minds That Feel

West Dean GradCert

Autumn 2020

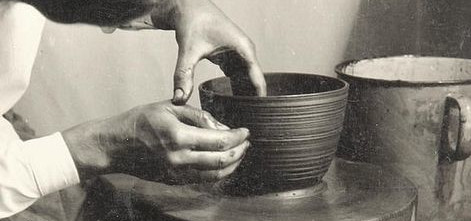

In our first week, we will ask what thinking has to do with making; logic to do with creating; or mental tools and faculties to do with manual tools and skills. Most importantly, we will ask what we might want art and thought to have to do with each other?

We will consider the legacy of Classical, Judaeo-Christian and Enlightenment thought on how mind and body are understood, and how these ideas influence our definitions of “art” and “craft”. We will examine terms like criticism, critique and criticality; and consider some alternative traditions of understanding hands, brains, tools and souls.

Required Reading

Ibn Rushd (Averroës), “On the Immateriality of the Intellect: The Chapter on the Rational Faculty Middle Commentary on Aristotle’s De Anima, Sections 286–290”, translated from the Arabic by A. L. Ivry, in ed. G. Klima et al. Medieval Philosophy: Essential Readings with Commentary (Oxford: Blackwell, 2007), 200–201.

Souleymane Bachir Diagne, “Introduction: The Initial Philosophical Intuition”, African Art as Philosophy: Senghor, Bergson and the Idea of Negritude [2007], trans. Chike Jeffries (London: Seagull Books, 2011), 3–17.

Gregory Bateson “Foreword” and “Metalogue: Why a Swan?” [1954], Steps to An Ecology of Mind (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 1 + 33–37.

We will pick up on some of the ideas from our first week together to interrogate the place of tools in producing different kinds of relations between our bodies, brains and the world. We will look at particular art practices and apparatuses including photography and weaving, and ask how the particular histories of technologies such as twine, looms, celluloid and microchips affect their use as artist tools. We will go on to consider the ways in which the different objects and gestures of making are available to us as schematic and poetic “figures of thought”.

Required Reading

Vilèm Flusser “Fingers” [1979], Natural:Mind, trans. Rodrigo Maltez Novaes (Minneapolis, MN: Univocal, 2013), 57–63.

Donna J. Haraway “Playing String Figures with Companion Species”, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Cthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), pp9–16 + pp34–35.

This week we will address the seemingly traditional questions of composition and the relation between content and form. We will look at the historical background of these analytic questions (for example, in the modernism of Matisse, Hammershoi, Gego and Rodin) before looking at how they were later re-stated in more dynamic terms. Composition was recast in terms of centrifugal and centripetal forces – leading to ways of “mapping” surfaces and forms which did not rely on external reference points – and distinctions were blurred between form and content, matter and meaning (for example, in works by Lydia Clark, Louise Bourgeois, Saloua Choucair and Helen Marten).

Readings come from the group of thinkers around October, the influential MIT arts journal established in 1976 with the express purpose of developing post-structuralist art theory in the English-speaking world. As such, we will take the opportunity to familiarise ourselves with some of the seminal names and claims surrounding the theories of structuralism and its progeny.

These approaches can produce particularly difficult texts, so this week especially we will be attentive to ways of navigating dense and complex pieces of writing.

Required Reading

Rosalind E. Krauss “Grids”, October Vol.9 (Summer, 1979): 50–64.

Yve-Alain Bois & Rosalind E. Krauss “Preface” + “Horizontality”, Formless: A User’s Guide (Cambridge, MA: Zone Books, 1997), 9–10 + 93–103.

LIVESTREAM FIELDTRIP—WORKSHOP

Mudlarks and Enterprise Zones

A livestream educational and pedagogicogeographical ramble around London’s Docklands, exploring “the art of walking” and the ways in which art, planning and archaeology have affected the area. Access allowing, we will finish the fieldtrip by getting our hands dirty and reflecting on history is structured, revealed and deconstructed by time, tide, mud and artefacts.

This week we will consider how power and knowledge condition each other, with particular attention to art institutions and their academic gatekeepers. We will ask how canons and orthodoxies are established and maintained; look at the history of explicitly rejecting these authorities compared with setting up alternatives; and ask how these concerns might allow us to reflect on our own exhibition practice, gallery visits and research.

We will consider examples from history and myth, from Athena’s melding of jurisprudence and jurisdiction in Aeschylus’ Oresteia, to discussing how authority and representation are foregrounded in works by Claude Cahun, valie export, Martha Rosler, Womanhouse, Adrian Piper, the Guerilla Girls, Coco Fusco and Ingrid Pollard.

Required Reading

Linda Nochlin, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” [1971], The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader (2nd Edition), ed. Amelia Jones (London: Routledge, 2010), 263–267.

Aeschylus, Eumenides in The Oresteia Trilogy and Prometheus Bound, trans. Michael Townsend (Scranton, PA: Chandler Publishing, 1966), ll452–765 [pp84–91].

This week we will look at how ideas of work and self were recalibrated throughout Britain in the 1980s and ’90s. By taking in the denigration of manufacturing and class politics; the rise of postmodernism, financialisation and the information economy; and the celebration of individualism (on the right) and identity politics (on the left), we will explore the material, historical crucible from which emerged many of our current notions of truth, meaning and worth. Given the “mainstreaming of the alternative” that accompanied the rise and consolidation of neoliberalism, what legacy did the era leave today’s artists?

We will consider the “YBAs”, asking how their practices, exhibition spaces and public personae have evolved since the days of Cool Britannia; and we will examine works by Yinka Shonibare, Rosalind Wyatt and the Hayward Gallery exhibition History is Now: Seven Artists Consider Britain (2015) to reflect on how history and memory can be re-presented through information, images and materials.

Required Reading

A. Sivanandan “Part I, All that Melts into Air is Solid” Full version in A. Sivanandan, “All that Melts into Air is Solid: The Hokum of New Times” [1990], Communities of Resistance (London: Verso, 1990), 19–59.

Screening

The Gleaners and I, dir. Agnes Varda, 2000

“this is my project: to film with one hand my other hand.”

By considering the role of art in public space we will examine the notion of “the public”. A crowd has behaviours, a group has an identity; what does it mean that the public has an opinion or sensibility, and that these are somehow both collective and contested; consensus and dissensus? Does a new notion of “the public” emerge in relation to an artwork, in relation to a gallery, etc.? We will examine the examples and theory Miwon Kwon uses to explore how site specificity and publics intersect and mutually affect each other; and we will ask whether these ideas are useful for us in thinking through current and historical issues around art, communities and public space – for example by considering the toppling of a statue of Edward Colston in Bristol in June, and the subsequent controversy around Marc Quinn and Jen Reid’s “collaboration” to install a replacement work.

Required Reading

Miwon Kwon “The (Un)Sitings of Community”, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004), 138–149 (+pp201–206)

Rasheed Araeen “A Question of Knowledge: Rasheed Araeen Interviewed by Tim Smith-Laing”, Frieze 183 (Oct 2016).

Annotated Screening

Grey Gardens (dir. David and Al Maysles), 1975.

This week we will consider the ways in which aesthetic values and social norms have been subverted by artists. We will consider ugliness, old age and decrepitude, deformity and sickness, poverty and obesity. We will be discussing works which confront, and those which operate more subversively to undermine expectations – analysing what strategies are used and asking what ends are sought. We will consider the wider cultural scenes in which these rebellious and seditious works emerged – from the decadent and gothic traditions through the underground railroad to surrealism, punk, “second wave” feminism and performance art. We will consider artists from Unica Zürn, WeeGee and Jenny Saville to Paula Rego, Kara Walker, Jessica Stollers and Jo Spence.

Required Reading

Frances Hatherley, “Delicious Decay – The Laugh of the Grandmother: Images of the Female Grotesque in Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet and David and Al Maysles’ Grey Gardens”.

Kin, Care, Kindness & Reworlding

West Dean MFA

Spring 2021

“Now dance the lights on lawn and lee”. The days lengthen and the dark becomes more precious; shoots emerge and tails are docked. Imbolc announces spring!

Throughout this term, we will continue our exploration of aesthetics as the ongoing, open elaboration of embodied thought. Primary amongst our concerns over these eight seminars will be the expression of worlds. This is meant in at least two senses:

the refinement of our capacity to co-elaborate worlds of matter and meaning

(ethico-aesthetic ecologies of making-with); and

the cultivation of our openness to the world-as-expression

(aesthetics as the offering of our sensibility to other/s and the outside).

In the Spring term, our discussions will turn toward relations and otherness in everyday, artistic and parapolitical contexts. Against a backdrop of sociopolitical moral one-upmanship, hyper-public virtue signalling and heresy-policing “call outs”, we will ask instead how artists and other embodied thinkers develop everyday habits, ethics, relations, comportments, encounter-catalysts and anomaly-lures to sustain and nurture an ecology – indeed, an ecosophy – of difference.

The term will be split into two blocks: the first looking at relations and the sustenance of the more-than-one, with a particular accent on love, cultural memory, freedom and participation; and the second looking at the ways in which “others” are understood, encountered, feared, loved and entered into becomings with.

In addition to developing a critical vocabulary and familiarity with the sources, we will be particularly concerned with how artists have sought to produce audiences and publics differently, have foregrounded “non-art” spaces, materials and processes, have incorporated highly personal stories into their work, and have nurtured archaic or idiosyncratic belief systems.

Lectures and seminars will draw on a broad and eclectic range of sources including and exceeding the visual arts, and we will encourage reflection on personal experience and studio practice as part of our discussions.

We will begin the first block by providing context to the return of love and friendship to the foreground of contemporary “continental” philosophy. How do we go about understanding relations that are not exclusively socio-political? What value do we place on a truth that seems so subjective – so universal yet so singular and exceptional? Is this knowledge that love generates an “epistemopathy” whereby we are more concerned with the feeling of knowing than with the Enlightenment principles of iterability and falsification? Is it right to privilege “two” when thinking (about) love?

In Alain Badiou’s thought, love constitutes one of the four “conditons” of philosophy. If, as he argues, “no theme requires more pure logic than love”, he seems to be negating the whole history of courtly and romantic thought which, since Plato has understood love as the one true exception to mathematical logic. Yet, for Badiou, if love confirms the philosophical operation of “counting”, it also establishes, through non-mathematical procedures, another number: “two”. Where in Plato’s Symposium Aristophanes asserts that love “tries to make one out of two and heal the wound of human nature” (Plato, Symposium 191d), for Badiou, love is not at all the sticky stuff that brings our tragic fragments back to a quasi-divine unity. Where “the One” or “the logic of the same” invokes a universalising God, phallus, or Truth etc., the indissoluble “two” made by love, asserts a place for difference and the multiple that is higher than – not subordinate to – the One.

Required Reading

Alain Badiou, “Love and Art" in In Praise of Love trans. Peter Bush (London: Serpent's Tail, 2012), 77–94.

Luce Irigaray “13: Practical Teachings: Love – Between Passion and Civility” in I Love to You (extract) (London: Routledge, 1996), 129–131.

If for Badiou “Love” names an irreducible “two-ness” which guarantees the possibility of universalism without destroying sexual difference, Chantal Mouffe argues that the reinvigorating of oppositional difference is the only means of saving democracy. The democratic interrelations of a small-p-political public do not, she argues, rely on a mutual drift to the centre, to the muddy and acquiescent blandness of liberal technocracy, but rather to the reframing of antagonism as “agonism”. It is an argument which has heavily influenced Claire Bishop’s writings on participatory art, not least on the work of Thomas Hirschhorn. It is also a theme which novelist Anthony Cartwright has explored in several of his books, exploring the difficulties of living and loving in the face of profound disagreement: from families in the 1980s split by their responses to Thatcher, to lovers during the Brexit referendum.

This week we will consider the purpose of disagreement, with particular attention to the ways in which it is generated and itself generative, not least as regards public space.

Required Reading

Chantal Mouffe “Which Public Sphere for a Democratic Society?”, Theoria (June 2002): 55–65.

Anthony Cartwright “Black Country: An Essay in Response to the EU Referendum” in Iron Towns (2nd ed.) (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2017) 283–289.

We have seen in the previous sessions that love and agonism are “counts of two” which catalyse world-making (aesthetic events) and facilitate commitment to world-sustaining (ethical paradigms). This week we will consider the importance of site and memory in these two procedures in order to ask how belonging can be produced and affirmed not through rhetorics of “blood and soil”, but through multiplicity, difference and relationality. In doing so, we will come to ask if we might celebrate the potential of the excluded (“those who do not count”) without romanticising the perditions of the reified, the stateless and the “sans-papiers”.

As well as gaining familiarity with some of the ideas and vocabulary of Édouard Glissant’s oeuvre, we will look at the work of a number of Black British and British Asian visual artists – including Riz Ahmed and Helen Cammock – and at artists from the francophone Caribbean.

Drawing on the importance of the sea in Glissant’s thought, we will also consider the ways in which the laws of international waters have be leveraged in the activist art of Women on Waves, in particular A-Portable.

Required Reading

Édouard Glissant Poetics of Relation [selections]27,37-42,46-47,169-170,215-220

“Imaginary”, p1 ; “Errantry, Exile”, pp11–16, 20–21 ; “Root Idenitity, Relation Identity”, pp143–144 ; “For Opacity”, pp189–194.

Aragorn Eloff “Wandering the Shoreline with Édouard Glissant”, New Frame (7th May 2019)

Screening

VESSEL, dir. Diana Whitten, 2015

In the final week of this first block, we will look at materiality, ontology and cosmology as organisational social forces across and between cultures, and ask to what extent these are compatible with the dominant social paradigms of liberalism, multiculturalism and identity politics. For Elizabeth Povinelli, within late or neo- liberal society, love provides a glimpse of minimal difference: in love, the sovereign freedom of the individual and the constraints of context are most purely articulated and their ultimate contradiction is most keenly felt. This, for Povinelli, makes “love” a paradigmatic means of thinking about the governance of “others” (in particular, in her work, of Indigenous Australians by whites) for whom the distributions of self/society – not to mention the place of obligation and the immanence of history – are quite different from those inherited from the West.<br> For Povinelli, the collapse of multicultural diversity into liberal universalism mirrors that which is unveiled in love’s ambiguity (the love that is irreducibly “mine” is contradictorily something which happens to me, which I do not wilfully call upon myself).<br> As well as continuing our expansive discussions on the theme of love, we will look at the role of art practice in Povinelli’s living-with Indigenous Australians, from her drawing to her membership of the Karrabing Film Collective. Ultimately, we will ask to what extent Art, too, might be thought of as scrambling and smudging liberal values; and what supplements to freedom (of expression) and knowledge (of history) might be involved in thinking Art beyond liberalism.

Required Reading

Elizabeth Povinelli & Kim Turcot DiFruscia “Shapes of Freedom: A Conversation with Elizabeth A. Povinelli”, e-flux #53 (March 2014)

Study day on the films of Kornél Mundruczó

White God (2014) & Jupiter’s Moon (2017)

In the first week of this second block we will look at the way in which Hungarian filmmaker Kornél Mundruczó has sought to represent the “otherness” of refugees. Seemingly less concerned with the evident institutional forces which create and control borders and the “legitimacy” of individuals, Mundruczó uses fantastical analogies to explore how refugee crises might not only have a moral charge, but might also offer alternate ethics for being in the world with others. He is thus a provocative guide to questions around the positive potential of imagination and fabulation in our encounters with and portrayal of “others”.

Required Reading

Extract from Ghassan Hage “Islamophobia and the Becoming-Wolf of the Muslim Other” Is Racism an Environmental Threat? (Cambridge: Polity, 2017), pp37–51.

This week we will consider extraction and excretion – which is to say, the exploitation and exclusion of nonhuman others. We will consider how “big” agriculture and food production has foregone its cyclical nature, attacked eco-diversity and eroded the mineral complexity of everything from soil to animal fats. We will trace these questions inside our bodies to consider our microbiological complexity, its degraded seasonal variations and the limits of being human in a human body.

Throughout, we will foreground an expanded understanding of pasture – an ecology of process over property, in which all manner of biochemical processes are entangled. More than providing a balanced diet for grazers and encouraging healthy soil, pasture-being eschews both the extractive imperatives of infinite growth and the blunt managerial abstractions of agrichemical boom-bust monocrops. We will ask how waste has been repositioned in contemporary society – from the rhetoric of “reduce-reuse-recycle” to home composting – and how our waste both affirms and disrupts our sense of self. The set readings frame these debates in terms of gender and property/territory in particular.

Inevitably, we will encounter questions to do with the ownership and institutionalisation of knowledge, and ongoing debates around the process-product calculus of art making.

Required Reading

Vandana Shiva “Women Feed the World, Not Corporations”, in Who Really Feeds the World? The Failures of Agribusiness and the Promise of Agroecology (Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books, 2016), 111–124.

Michel Serres Malfeasance: Appropriation through Pollution? trans. Anne-Marie Feenberg-Dibon (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2011), 1–17.

We will return to the work of Elizabeth Povinelli, in particular her investigations of how non-human agency can be genuinely respected within our systems of government. Looking at examples including the rights of riverbeds, mountains and fogs, we will push the boundaries of what is meant by “personhood” beyond any correlation with biological life. We will briefly consider some of the panpsychist and “vibrant matter” theories of twentieth century western thought – including their influence on artists from Katrina Palmer to Lucio Fontana – and look at how art and aesthetics has or can lead the way in the more-than-human political problem of respecting the rights of the silent, slow and enormous “others” of geology, weather and place.

Required Reading

Elizabeth Povinelli “Geontologies: The Concept and Its Territories”, e-flux #81 (April 2017).

Jeffrey Jerome Cohen “Excursus: Geologic” in Stone: An Ecology of the Inhuman (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2015), 187–193.

Death and finitude rose to dominate much of twentieth century Western philosophy, from the works of Martin Heidegger to the heroic-tragic absurdities of existentialism.

In Torajan culture, the dead remain a part of the household for many years, and even after burial are often disinterred so that the corpse can be cleaned and given a change of clothes (Ma’nene). In parts of West Africa, a friend or family member is appointed annually to eat the favourite foods of the deceased. Closer to home, British occultist Peter Gray has observed that perhaps the most “witchy” thing one can do is to tidy one’s local churchyard.

Altogether, little has generated as much ritual and taboo as death and the dead. But what if we look past the existential and anthropological meaning of rites and representations of death, and think instead about the material and lively proximity of the dead?

In a day of discussion, workshops and adventures, we shall attempt to think about relating to the dead, what it would mean to cultivate a proximity to this intimate other, to acknowledge our co-extension or “being-with”. Rather than invoking the dominant cultural modes of relating to the dead – namely, mourning and horror, both of which tend to divide memory and matter – we will seek instead to investigate ritual, care, kindness and credulity. In this way, we will ask how we understand our own relationships to death, history, kinship and otherness.

Required Reading

Jake Stratton-Kent “What is Goetia; Cthonia Lost; Cthonia Regained”, in Geosophia: The Argo of Magic I (Scarlet Imprint, 2010), i–xiii.

William Faulkner As I Lay Dying (I would recommend the Norton Critical Edition, but any edition will do fine – the book pops up frequently in charity shops and other secondhand sellers)

Workshop

Exploring Ancestor Care (including graveyard tidying around the estate)